It took one year for Dona Krystosek to get a diagnosis for her son, Levi, after he was born. The family received three misdiagnoses of fatal diseases until they found out Levi has Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia — an extremely rare form of dwarfism.

“The hardest thing for me to handle [about] … not getting an immediate diagnosis of what was wrong with him was I couldn’t understand,” said Krystosek, who lives in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. “What do you mean you can’t tell me what my son has?”

During Newborn Screening Awareness Month, marked each September, advocates hope that future parents can avoid the same “diagnostic journey.” They aim to educate the public on the importance of screening, which is typically done 24–48 hours after birth.

This month — which included bipartisan congressional briefings, webinars, and social media initiatives — is ending on Wednesday, but for Julia Jenkins, executive director of EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, the work has just begun.

“We started hearing from our community,” Jenkins told BioNews Services (which publishes this website) in an interview. “Patients would give us a call and say, ‘Newborn screening is a broken process. It cannot be fixed by individual disease organizations.’ ”

‘A continual burden’

The foundation started in 2009, initially focusing on regulatory policy. After working on newborn screening in 2017, the organization expanded its mission statement to include diagnostics.

According to Jenkins, not all states are following the recommended uniform screening panel, a list developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which includes screens for 35 core disorders and 26 secondary disorders, including spinal muscular atrophy, cystic fibrosis, and sickle cell disease. All states screen for at least 31 disorders, while nine screen for the full list.

Jenkins said the responsibility of adding a disorder to the recommended screening panel falls on the patients. For a disorder to be considered, individuals have to submit a nomination package, which includes supporting scientific data, to the Committee for the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel. However, the Secretary of HHS makes the final nomination, and even then, states aren’t required to test it.

“It’s just a continual burden on our patient community to now have to do this for their community,” Jenkins said. “We see our role as the foundation to try and alleviate this burden.”

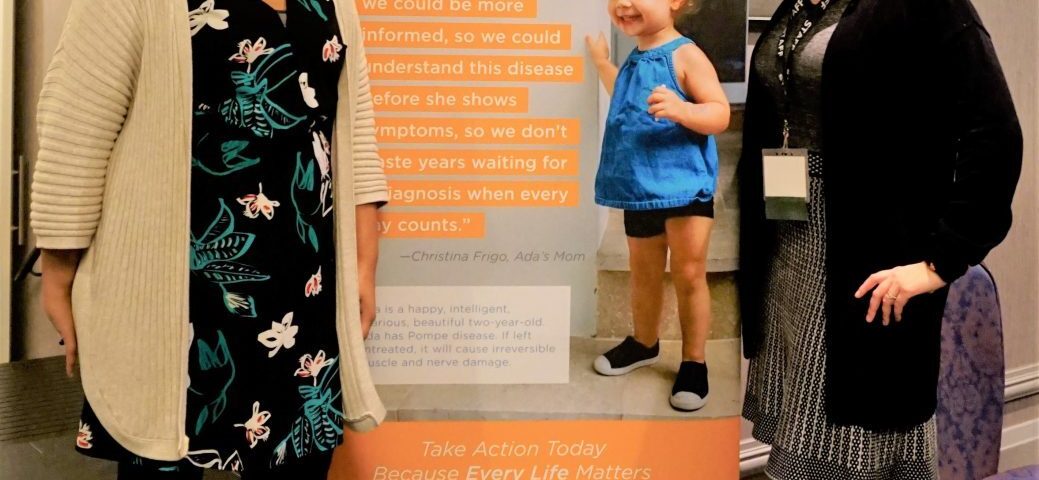

It’s not easy to add a disorder to the recommended screening panel, even if there is an approved treatment, Jenkins said. Pompe disease has had a therapy approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for 10 years — Lumizyme (alglucosidase alfa) by Sanofi Genzyme — yet many states are not screening for it.

Advocates should be thinking about nominating a disorder to the federally recommended screening panel long before a treatment is approved, Jenkins added.

Filling in the gaps

“If you’re enrolling in clinical trials, you should be also looking at funding your newborn screening plan for your disease, especially when there are early-onset pediatric diseases,” Jenkins said. That would reduce the gap between a treatment being approved and a disease getting added to the screening panel.

Starting Sept. 30, EveryLife and Expecting Health at Genetic Alliance will co-host their second newborn screening boot camp to help people, patient advocacy organizations, and industry players understand the screening panel nomination process and ways to improve the existing testing infrastructure. Registration for the program is open.

As part of Newborn Screening Awareness Month, the bipartisan and bicameral (House and Senate) Congressional Rare Disease Caucus hosted a virtual briefing on screening and diagnostic testing Sept. 22. Kathleen Tighe, head of U.S. public affairs and patient advocacy for Sanofi Genzyme, moderated the briefing, which included Krystosek, a legislative health policy advisory, and a public health genetics contractor.

While media were prohibited from quoting directly from the briefing, Krystosek told BioNews Services that newborn screening could save the government money in the long term by getting proactive with treatments.

“All the children in America deserve a chance at a pain-free, productive outcome and good quality of life,” she said. Krystosek is also the family outreach coordinator for Miracle Flights, which provides free flights for patients to receive needed medical care.

The EveryLife Foundation runs the related Rare Disease Legislative Advocates program and held its own webinar Sept. 10. Patient advocacy representatives spoke about the urgency of reauthorizing the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act and working with states to add more disorder screenings.

Sessions Cole, MD, a newborn physician at Children’s Hospital St. Louis and professor of pediatrics at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, also presented findings from the Undiagnosed Diseases Network, for which he is a principal investigator. The research study at 12 clinical sites across the country is funded by the National Institutes of Health, and aims to do what its name suggests — solve medical mysteries, particularly among children.

Some of the network’s early findings showed it was able to diagnose 35% of the 382 patients who were enrolled. Since those numbers were released in 2018, an additional 47 people have enrolled. Researchers have discovered 30 new diseases as a result — disorders that may eventually make the recommended uniform screening panel.

COVID-19 has added another challenge to ensuring diseases are screened accurately and on time. States use public health labs to screen newborns and also process COVID-19 tests. Jenkins said the state labs are underfunded, and now they are overburdened with tests.

Newborn screening legislation

The cost associated with testing is part of what EveryLife hopes to address in the legislation it writes. Funding is one of the three pillars — along with a deadline and adherence to the screening panel — that make its bills successful, Jenkins said.

Each state needs varying levels of funding depending on the number of newborns (3.3 million babies are projected to be born in the U.S. between March 11 and Dec. 16), technology, and the efficiency of the tests. It should cost a few cents or dollars to get a test out the door, Jenkins said. That’s where the federal law on newborn screening comes into play.

In September 2019, funding ran out for the federal Newborn Screening Save Lives Reauthorization Act (HR 2507), which was passed in 2014. According to a March of Dimes fact sheet, the bill primarily gives grants to states so they can “expand and approve their screening programs.” The Reauthorization Act would amend the existing legislation to appropriate $60.6 million every year until 2024.

The House passed the bill last July, but it’s still held up in the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, where it must be marked up, passed by the Senate, and signed by the president. Because of privacy concerns, Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) introduced an amendment that would require parents to opt in for unidentified blood samples of their baby to be used for research.

Advocates, including Jenkins, argue that adding informed consent would hamper continued development of more efficient screening tests and breakthroughs in rare disease treatment.

“That would be a tragedy,” Jenkins said.

The EveryLife Foundation has also started working within state legislatures to ensure all the recommended disorders are screened. So far, they’ve had success passing laws in the California and Florida legislative branches. The Georgia House of Representatives bill passed unanimously, but lawmakers went on recess before it got to the state Senate.

Apart from passing legislation, another goal of Newborn Screening Awareness Month is to inform parents that they can have their child tested in the first place. Parents are so busy with the birth of their child that they often overlook newborn screening, Jenkins said. In addition, informing the public about newborn screening can help maintain support for the program.

“This is a public health program. It’s not just about rare diseases,” Jenkins said.

Nurses, for instance, test for any hearing issues at birth. “It’s the most successful public health program out there,” she said.